Poohsticks Is the Way

Rev. Douglas Taylor

June 16, 2024

Sermon Video: https://youtu.be/UL5J6M6QBFw

Back when I was in seminary, I took a survey course on Eastern religions traditions, learning about Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Shinto primarily – a hint of Hinduism was included at the beginning. But the tradition that most captivated me was Taoism. And I remember my final paper was about the difference between the grand traditional gardens of Europe and the traditional gardens of China and Japan. The difference in the gardens illustrates a key difference in the worldview between the east and the west.

Traditional European gardens are all straight lines and rows, manicured box-shaped bushes, and flowers in matching colors. Traditional Japanese gardens on the other hand are echoes of the natural world brought into cities and homes – they are asymmetrical and feature rocks and water along with various plants.

When a gardening style rises to the level of being considered ‘traditional,’ it is in part because the garden represents something about the culture and how people see themselves. Where traditional European gardens are meant as an improvement on nature, the traditional Japanese gardens are in interpretation of nature. In our western philosophy, the natural world is seen as something that must be stewarded, improved upon, and controlled. It is a resource or an obstacle. But in eastern philosophy, Taoist philosophy in particular, the natural world is in balance and our goal is to emulate it, to learn to be in balance as well. It is perhaps fair to say they are both seeking a balance; but the balance of the European garden is static with sharp lines while the Japanese garden’s balance is dynamic and reflective of the natural world.

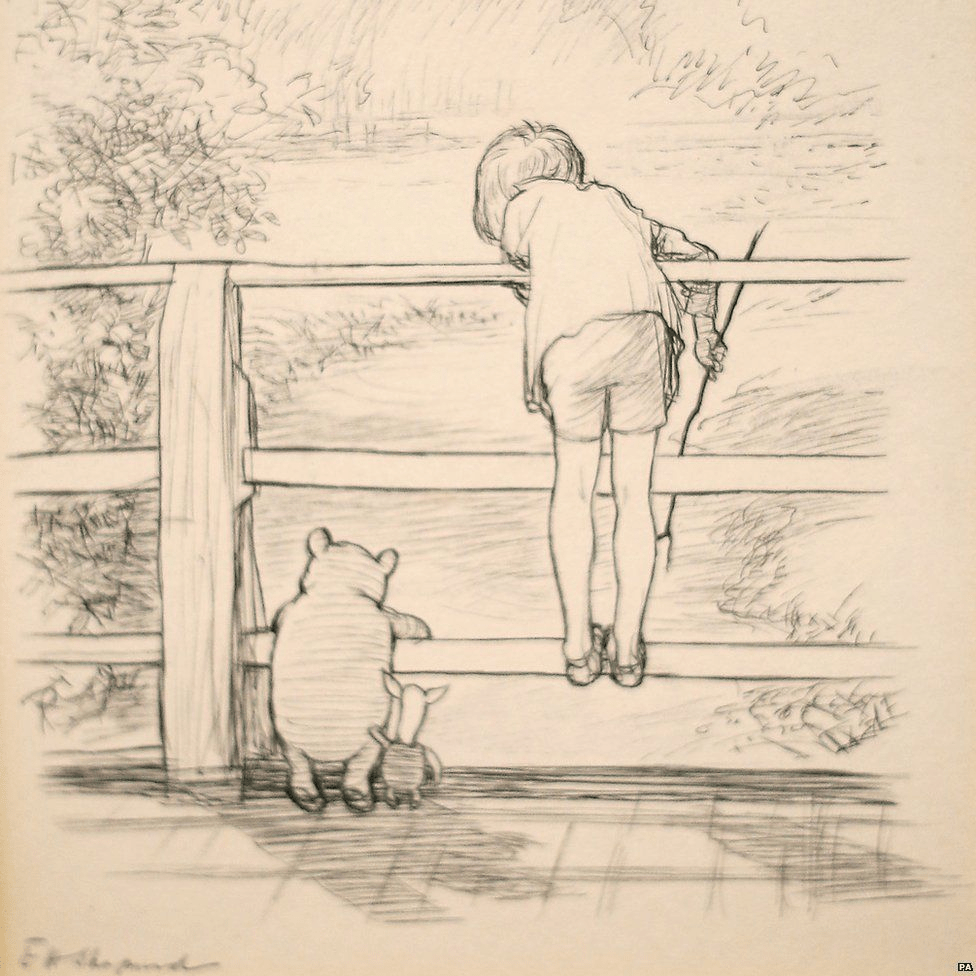

This more dynamic form of balance is a key theme in Taoism. And, in a playful way, is exemplified by the story of Poohsticks (which we heard at the Time for All Ages).

Lao Tzu is the first teacher of Taoism and the author of the book the Tao Te Ching. The first chapter of the Tao Te Ching states: “The Tao that can be expressed is not the true Tao. The name that can be named is not the true name.” This first stanza of ineffability has confounded and enlightened countless people through the centuries. It is a central theme throughout the text.

A second theme, the theme that is my focus this morning, is balance. In the second chapter we hear about a series of polarities: when we know about beauty, we become aware of the ugly. When we understand one thing to be good, that naturally means another thing is wicked. Long and short, high and low, before and after. The first two stanzas of the chapter carefully delineates the relationships that make our living. And then it says this:

“That’s why the wise soul does without doing, teaches without talking. The things of this world exist, they are; you can’t refuse them. To bear and not to own; to act and not lay claim; to do the work and let it go; for just letting it go is what makes it stay.” (Le Guin translation)

In Taoist philosophy the goal of life, the grand purpose, is balance. So much of our living is out of balance. The wise soul seeks to maintain and even restore balance. And there is a nuanced way to understand what is meant by this Taoist idea of balance. Toward that end, the wise soul – as it says in chapter 2 of the Tao Te Ching – ‘does without doing.’

How does one ‘do without doing’? The Chinese phrase being translated is “Wu-wei” and the literal translation is “Not doing” but the tone of the phrase is still about doing something. It is not inaction. It is not ‘doing nothing.’ Many translators have used the English translation ‘effortless action.’ This phrase highlights how the action not being forced or pushed. Another way to think of it is to see the difference between the European garden and the Japanese garden. Both involve quite a bit of work; but one style forces nature into an unnatural form while the other is an interpretation of nature along natural lines.

Philosopher and author, Benjamin Hoff writes: “Literally, Wu Wei means ‘without doing, causing, or making.’ But practically speaking, it means without meddlesome, combative, or egotistical effort.” (The Tao of Pooh, p 68)

In his popular book The Tao of Pooh, Benjamin Hoff argues that A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh character is an example of Taoist practice – Pooh accomplishes a lot throughout the stories but he mostly stumbles into the solutions. He is just being Pooh. Milne makes Rabbit clever and Piglet anxious and Tigger incorrigible. Pooh just sails through the stories not really doing anything and yet that is his charm.

In our reading this morning, (https://www.mrdbourke.com/wu-wei/) Daniel Bourke titles his piece “The Art of Not Forcing.” He uses the distinction between rowing and sailing to make the point. “While the rower uses effort, the sailor uses magic.” When he says magic, he means the way the sailor does not push or force the boat to move; instead, the sailor arranges for the wind to move the boat. Wu-wei is still an action, but it is an action that does not force or push or run counter to the natural world. It seeks to move along natural lines.

What does this look like in our lives? In the Tao Te Ching, the concept is applied most directly to leadership and being the ruler of a country. The text often refers to ‘kings and princes’ and ‘the people.’ The best rulers do not impose or force the people to be in a certain way. Instead they assure that the people are not hungry.

Or think of this in terms of other leadership roles such as being a parent or a supervisor or a teacher. Maybe you are president of a board or chair of a department. Perhaps you are the point person or lead for a project or campaign. Whatever it is where you get to make the decisions that can impact not just yourself but other people as well; a role in which you wield some power.

How can you apply these ideas of the Tao and Wu-wei to your leadership role? Is there a natural wholeness and balance you can promote? Are there choices you can make that enhance the lives of the people?

Remember the goal is not to do nothing. It is to offer ‘effortless action.’ In a Japanese garden, the goal is not to let the space go wild. It is to craft an interpretation of nature; to shape a space along natural lines that reflects the dynamic balance of the natural world.

And here I will circle back to a small moment in from the reading by Daniel Bourke and the analogy of rowing and sailing. Perhaps you heard the acknowledgement that one could still row when needed.

To approach everything with Wu-wei. To not force. To let let let it happen. (Bourke wrote,) To put up a sail and ride the winds. But to row if you need to. Because even effort can be applied effortlessly. When you know the grand source.

Another author, Stephan Joppich, https://stephanjoppich.com/wu-wei/ also lifts up the warning against seeing Wu-wei as non-action or surrender. Joppich says that what Wu-wei advises is we give up on forcing things, not that we give up altogether.

For instance, when you’re experiencing injustices, Wu-wei doesn’t suggest resignation. It’s quite the opposite. We-wei suggests a persistent amount of pressure. This pressure isn’t a metaphorical jackhammer or wrecking ball. It’s a soft strike in the right spot. It’s like water quietly working through the toughest cliffs and rocks.

Taoism does return to the metaphor of water quite a bit. Chapter 66 and 78 talk about water as a model for how to be in the world. Bruce Lee has a great quote about being like water.

“Be like water making its way through cracks. Do not be assertive, but adjust to the object, and you shall find a way around or through it.”

But perhaps the best example is from Chaung-Tsu, a Chinese philosopher and Taoist whose importance to the founding of Taoism is considered second only to Lao Tzu. Chaung-Tsu offers this story. (paraphrased from the Tao of Pooh, p68-9).

There was a great waterfall in a turbulent river. A wise teacher was watching the waters one day and saw an old man being tossed about by the water. The teacher called to his disciples and together they rushed down to the river to help the man, though they feared there was little they could do. By the time they reached the waters’ edge, “the old man had climbed out onto the bank and was walking along, singing to himself.”

Shocked and a little awed, the teacher inquired of the old man, “What secret power do you have?” But the old man laughed it off and said, “I go down with the water and come up with the water. I follow it and forget myself. I survive because I don’t struggle against the water’s superior power. That is all.”

In another chapter of Winnie the Pooh, in which Christopher Robin Leads an Expotition to the North Pole, one character has a very similar experience. Christopher Robin takes everybody on an expedition to discover the North Pole. They pack provisions and head out together in a line. Eventually, they stop for lunch in a nice grassy spot by a stream. After everyone is finished eating, a scene unfolds that is strikingly similar to that of Chaung-Tsu’s old man in the river.

—

Piglet was lying on his back, sleeping peacefully. Roo was washing his face and paws in the stream, while Kanga explained to everybody proudly that this was the first time he had ever washed his face himself, and Owl was telling Kanga an Interesting Anecdote full of long words like Encyclopaedia and Rhododendron to which Kanga wasn’t listening.

“I don’t hold with all this washing,” grumbled Eeyore. “This modern Behind-the-ears nonsense. What do you think, Pooh?”

“Well,” said Pooh, “I think—”

But we shall never know what Pooh thought, for there came a sudden squeak from Roo, a splash, and a loud cry of alarm from Kanga.

“So much for washing,” said Eeyore.

“Roo’s fallen in!” cried Rabbit, and he and Christopher Robin came rushing down to the rescue.

“Look at me swimming!” squeaked Roo from the middle of his pool, and was hurried down a waterfall into the next pool.

“Are you all right, Roo dear?” called Kanga anxiously.

“Yes!” said Roo. “Look at me sw—” and down he went over the next waterfall into another pool.

Everybody was doing something to help. Piglet, wide awake suddenly, was jumping up and down and making “Oo, I say” noises; Owl was explaining that in a case of Sudden and Temporary Immersion the Important Thing was to keep the Head Above Water; Kanga was jumping along the bank, saying “Are you sure you’re all right, Roo dear?” to which Roo, from whatever pool he was in at the moment, was answering “Look at me swimming!” Eeyore had turned round and hung his tail over the first pool into which Roo fell, and with his back to the accident was grumbling quietly to himself, and saying, “All this washing; but catch on to my tail, little Roo, and you’ll be all right”; and, Christopher Robin and Rabbit came hurrying past Eeyore, and were calling out to the others in front of them.

“All right, Roo, I’m coming,” called Christopher Robin.

“Get something across the stream lower down, some of you fellows,” called Rabbit.

But Pooh was getting something. Two pools below Roo he was standing with a long pole in his paws, and Kanga came up and took one end of it, and between them they held it across the lower part of the pool; and Roo, still bubbling proudly, “Look at me swimming,” drifted up against it, and climbed out.

“Did you see me swimming?” squeaked Roo excitedly, while Kanga scolded him and rubbed him down. “Pooh, did you see me swimming? That’s called swimming, what I was doing. Rabbit, did you see what I was doing? Swimming. Hallo, Piglet! I say, Piglet! What do you think I was doing! Swimming! Christopher Robin, did you see me—”

But Christopher Robin wasn’t listening. He was looking at Pooh.

“Pooh,” he said, “where did you find that pole?”

Pooh looked at the pole in his hands.

“I just found it,” he said. “I thought it ought to be useful. I just picked it up.”

“Pooh,” said Christopher Robin solemnly, “the Expedition is over. You have found the North Pole!”

“Oh!” said Pooh.

—

Effortless action. Pooh was not trying to find the North Pole. He was trying to help Roo. If you have some power, some role in which you have an impact on the lives of others – use it with, I would say, compassion. Use it in a way that will enhance the natural way of things. Or, as the Tao Te Ching keeps saying, use it to be sure the people are not hungry.

May we learn the difficult art of acting in ways that are true to our nature and in balance with the natural world. May we always work for the true natures of others to blossom and grow. When we see injustice or cruelty, may we recognize it as imbalance and seek to offer guidance and correction to restore balance rather than to add more harm. May we learn to do without doing. To teach without talking. To act and not lay claim. May we do the work and let it go. Then do the work again tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow – each day doing our part to restore balance to our too-often broken and unbalanced living.

In a world without end,

May it be so.