Know, and Be Not Still

Know, and Be Not Still

March 8, 2026

Rev. Douglas Taylor

Sermon video: https://youtu.be/HrUGJuAzVP4

Friends, there is a great amount of trouble swirling around us in our lives. Wars and violence, corruption and greed. I hear from many of you that you are struggling. With all that is going on, it is healthy – physically and spiritually – to step back from it all from time to time and breath. I asked you all a few months back to find your center, to build an altar, to get grounded. One simple and profound path is simply to breath with intention. To be still for a moment and breath.

One of my favorite meditations is by a colleague from a previous generation named Jacob Trapp who offers a lyrical ode to quiet stillness:

Let this house be quiet.

Let our minds be quiet.

Let the quietness of the hills, the quietness of deep waters, be also in us.

So quiet that the noise of passing events and present anxieties, of random recollections and wandering thoughts, is stilled. …

So quiet that we are renewed, we feel at one with all others, at home in a tabernacle of stillness.

So quiet that we sense the ripples of this pool of quietness and healing pass through us and out to the farthest star.

-Jacob Trapp

Do you have times of healing stillness in your life? The advice from Psalm 46 comes to mind. It is really a song about the protection God offers.

God is our refuge and strength, [it begins]

a very present help in trouble.

The Psalm goes on to say we need not fear because even though the mountains may shake and the waters roar, and even if the very earth should change – God is our refuge and strength. If nations are in turmoil and kingdoms seem about the fall – we need not fear. And near the end of the psalm we hear the line, sung as a quote directly from God,

Be still and know that I am God.

We can almost imagine what it is like during times of great turmoil and disaster – there is panic. People are in danger from the natural disaster or political upheaval. Perhaps we feel powerless and hopeless. Be still and know that I am God. When faced with trouble – the first thing to do, according to this Psalm, is to do nothing, to slow down, to look for God. Many people take this advice when the danger is less an actual earthquake and more the metaphorical kind. It is often good when in turmoil to take a beat, to stop or at least pause, allow your prefrontal cortex to catch up to what your amygdala has already suggested for solutions to the situation.

It is sound advice. I read once that the reason a long pause like this works is because your amygdala triggers your limbic system causing the ‘fight or flight’ response. But while the amygdala turns on like a switch, it does not turn off the same way. Instead, we must wait for the neurochemicals to dissipate. So, scientifically, being still and knowing God is an effective technique for dealing with situations like this. Being still and knowing God allows us to make a choice instead of having a reaction. It allows us to choose a response instead of a thoughtless reflex.

In our Unitarian Universalist circles, I suspect more of us nod in recognition about the amygdala than we nod in agreement about God. Allow me a moment on this point.

We Unitarian Universalists function as a multi-faith community. We gather around shared values such as love, justice, and transformation instead of gathering around shared beliefs about God or the Human Condition. I encourage us to become fluent in theological translation together.

If you believe in God and use that language when talking about your beliefs and spirituality – you may need to translate most Sundays when I am preaching. I will say ‘the holy’ or ‘Love’ or talk about our communal values that call us to be in the world in particular ways. When you hear me do that, you may need to stop and say to yourself – “Oh! He’s talking about God.”

If you are a pagan and you hear me talk about the caring for the environment or the beauty of nature, you may need to stop and say to yourself – “Oh! He’s talking about the Goddess.”

If you are an atheist and you hear me talk about ‘God’s love’ or quote from the bible, you may need to stop and say to yourself – “Oh! He’s talking about the high principles and deep values that guide our living.”

If you are a Buddhist and you hear me say, ‘be still and know that I am God,’ you may need to stop and say to yourself – “Oh! He’s talking about our Buddha-nature which we uncover through meditation and dharma study.”

I encourage us to all become fluent in theological translation here. Because we each have our own knowing and understanding. We each have experiences that have led us to see the world in certain ways that help us find meaning.

What does it look like in this exact example? “Be still and know that I am God.” Well, the Buddhists as I mentioned already have a deep understanding of what can be known when we are willing to be still. For pagans it might sound less like being still and more like going through the rituals or practices to reach the place psalmist is pointing toward. For atheists, the translation may sound like ‘be still and allow inner clarity to arise,’ or ‘be still and recognize what really matters in life before reacting.’

The important part is to tap into your centering values, our spiritual ground, the loving presence of God, that aspect of life that helps displace your ego and set you firmly in alignment with Love. You do not need to have a particular theology to have access to this experience.

“Be still,” the psalmist sings, “and know that I am God.” The advice is sound. It is good to stop and refocus when things are hard. And after the stillness, after the knowing, what’s next? It is worth noting that stillness is abnormal. When we are willing to ‘be still,’ we are doing something unusual – unnatural even.

Rev. David Bumbaugh once wrote “Silence is an abnormal state.” The same point applies to stillness, but hear what he says about silence:

Silence is an abnormal state.

The world is nowhere silent: the wind calls from the tree tops and whispers in the beach grass. …

Were our ears more finely attuned, we could hear the crack of granite as boulders are reduced to pebbles, pebbles to sand, sand to dust. …

The world is nowhere silent: birds sing and chirp, squirrels chatter, insects hum and whir.

They fall quiet only briefly at our approach, a suggestion that silence is a sign of fear.

Is it not strange that even as Gaia sings to us, calls to us, shouts at us, we seek wisdom in silence?

It is not a measure of our alienation that we retreat into silence, withdraw from the chorus, in order to hear the endless eternal song?

-David Bumbaugh

We are silent, Bumbaugh suggests, as a form of withdrawal from the ordinary way of things. And so it is with stillness too. Nothing is ever really still. We seek stillness as a temporary state to find clarity – not because we want to achieve stillness for stillness’ sake.

Painter Paul Gardner once said, “A painting is never finished. It simply stops in interesting places.” And the same could be said of nearly everything. It’s never finished; it simply stops in interesting places. The whole of existence is dynamic and changing.

Mount Everest, the huge mountain standing as a perfect symbol of massive, unyielding, constant, solid reality is “growing” about 2 millimeters per year as the continental plate under India pushes under the Asian Plate to its north. Meanwhile, sea levels around New York City are rising faster than in other places because the island hasn’t finished sinking into the earth’s crust after the glacial ice melt from the last ice age.

Nothing is still. The whole universe is alive and pulsing with sound and movement. Life is always changing and it is to life that we must stay true. Everything is in motion. Be still – God says. I can’t! My heart is beating, my atoms are swirling, my planet is spinning. I cannot be still. But I will pause, briefly, Oh God, I will pause and listen for what might be next.

Author Scott Russell Sanders writes a little about this in his book of essays entitled Earth Works (2012),

Since Copernicus, we have known better than to see the earth as the center of the universe. Since Einstein, we have learned that there is no center; or alternatively, that any point is as good as any other for observing the world. I take this to be roughly what medieval theologians meant when they defined God as a circle whose circumference is nowhere and whose center is everywhere. If you stay put, your place may become a holy center, not because it gives you special access to the divine, but because in your stillness you hear what might be heard anywhere… All there is to see can be seen from anywhere in the universe, if you know how to look. (p123)

The point of being still is to better learn how to listen, how to look, how to know life. Don’t be still, thinking if you can only be still enough for long enough you will somehow win. The universe doesn’t work that way. God doesn’t work that way.

Be still and know. Yes. And after the stillness, after the knowing … be not still. All the world is in motion. There are wars and violence happening around the world and in our own streets. There is trouble clamoring for our attention. When anger or impatience arises in your heart, when your neighbor or your kin causes you to want to lash out, when the mountains shake and the waters roar, when nations are in turmoil – when you feel lost or hopeless, unmoored – be still, be still, be still.

Say a prayer. Go walk in nature. Write in your journal. Perform a ritual. Sit in meditation. Gaze upon a beloved. Light a candle. Seek God. Be still. And know … know you are loved, know you have power still to affect your days, know you are not in this alone, know we can and will rise to better days, know God. Be still and know. And then … then … rise up and move.

In a world without end

May it be so

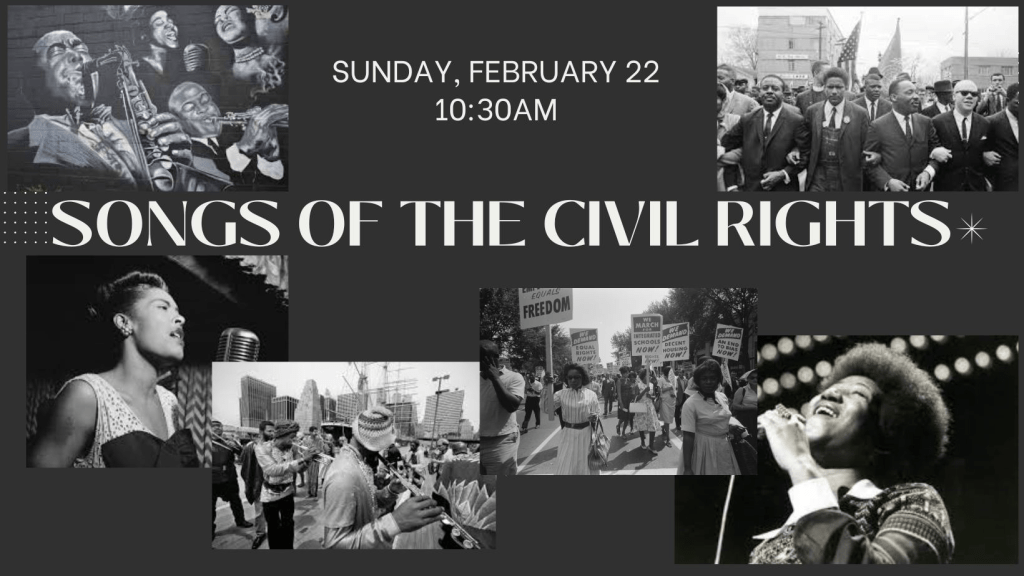

Songs of the Civil Rights

Songs of the Civil Rights

2-22-26

Rev Douglas Taylor and Dr. Sarah Gerk

Sermon video: https://youtu.be/tkNKonpW4yk

Sermon part I

Sarah

We are here today to consider how musical practices supported the Civil Rights movement. I am a musicology professor at BU. I study how music works within communities, primarily considering immigration, diaspora, and race in the United States during the 1800s.

When many of us hear “music of the Civil Rights movement,” we think about the music of protest actions. But it is a small part of the wide body of music that we professionals consider significant to the work of the Civil Rights movement. Music helps us in so many ways to regulate or foment emotional experiences, to form communities, and to broadcast information across a large community. In the 1960s, the popular music industry and recorded sound were relatively new, incredibly powerful tools for disseminating historical, emotional, and social information across the world, and we call your attention to this.

Today, Doug and I wish to explore how Black communities used jazz and popular music styles to create and assert their narratives. One of the most celebrated examples from the 1960s is John Coltrane’s Love Supreme, a jazz album that takes no received forms (so, it doesn’t adhere to the verses and choruses or blues chord progressions that are more familiar) to communicate Coltrane’s spiritual awakening to Islam in the early 1960s, finding his peace and sobriety in a violent and loss-filled moment.

My piece in this is to help you to understand the sound world of Black American music—how music that is not organized like our hymns and choir songs, which are typically conceived through music notation by thinking about melody, harmony, steady tempos, and song form, but instead on practices that stem from Africa and have developed in the New World, that come to us through Black churches and that place a lot of value on individual testimonies of spiritual experiences and personal narratives that would not survive or be understood in any other way. As we go along, I will help you to hear the ways that the music itself—the sound and not just the words—is working on us as it did in the 1960s to advance empathy, to help us process difficult information, and to find resilience.

Douglas

Dr. King once said,

It may be true that the law cannot change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless. The law cannot make a man love me, but it can restrain him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important also (Ware Lecture, 1966)

There were clear goals during the Civil Rights movement. People wanted desegregation, equality, real access to voting, access to education and jobs – they also wanted to put a stop to lynching. One goal we don’t talk about a lot was to have white people stop murdering black people with impunity. Which is still a conversation through the Black Lives Matter movement in our current time.

The song Strange Fruit is from 1939. It is based on a poem by Abel Meeropol, child of Russian Jewish immigrants, and it is a shocking song about the racial terrorism of lynching. Some say Holiday’s version marks the beginning of the civil rights movement. It is an unsettling and profound witness that can move you if you’ll let it. Consider that the trigger warning.

Sarah

Billie Holiday, one of jazz’s most celebrated vocalists, had an incredibly powerful voice. The grit of her voice itself, shaped by her strength to perform across Jim Crow’s America as well as adverse childhood experiences and substance abuse, contains a powerful message about who she is and how she feels. Billie’s expressivity comes in the ways in which she treats what would be a musical score—the map of the song—quite freely. Billie hardly ever stays on pitch, or in tempo. She scoops and slides her way around what would be a notated pitch. With the difficult material of “Strange Fruit,” she is often sagging below the scalar pitch, and lagging behind the tempo.

The first words of this song are “southern trees bear strange fruit.” The fruit are the corpses of lynched people. Listen to the words “bear strange fruit” and how they sag below the Western pitch. You may not be able to hear with your ear the gradations of microtone, and that’s ok. You can also feel it. It sounds off. Distressing. Clashing. Also hear or feel how she takes her time with those words, emphasizing them and slowing down a little, while the orchestra maintains a steady tempo. That is Holiday’s musical testimony to her own grief.

Video Strange Fruit by Billie Holiday

Douglas

One list I found, ranking the important songs of the Civil Rights Movement puts Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come as the number one, most enduring song of the movement. https://www.azcentral.com/story/entertainment/music/2025/01/28/best-civil-rights-protest-songs/77978742007/

Sam Cooke was certainly among the most influential soul singers of all time. His murder in 1964 was tragic, and the conclusions of the investigation are questionable. His death is sadly one of many Black murders during the movement.

A Change Is Gonna Come talks about Cooke’s experiences with segregation and racism. He performed the song on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in February is 1964, but the network did not keep a copy of the tape from that night. And when the Beatles played at the Ed Sullivan theater two days later – Sam Cooke’s performance was overshadowed.

The song was in the album he released that spring, but it was not released as a single until after his death in December of ’64. And yet, despite the many ways the release missed the audiences – this song ranks among the most influential songs of all time. The song is both anguished and hopeful, a remarkable blend of despair and defiant resilience.

Choir A Change Is Gonna Come by Sam Cooke

Sermon part II

Sarah

Part of the work of Black musicians in the 1960s was to assert Black identities and Black power in a musical world that had been heavily shaped by white commercial interests. Rock ‘n’ roll of the 1950s was an incredible moment in which Black music got lots of attention and some people made a lot of money. But we can also name it as a historical moment of white appropriation of a powerful tool for Black communities.

Funk represents a backlash to this. Structured around an interlocking rhythmic pattern in the electric bass [MAYBE DO A LITTLE BOOTSY COLLINS IMITATION] and the drum set, the remaining instruments and vocalists layer their own patterns on top. Repetition is the structure, and that allows for individual and group emotional expressions or testimonies on top of that structure. Again, pitches and melodies are significantly less important than much of the music we practice here on Sundays.

Significantly for this particular song, James Brown invites Black communities to say repeatedly together “I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Musicologists have a term “unisonance” that describes the ways in which creating sound together can be a powerful tool for fostering a feeling of connectedness. Here, James Brown uses the tools of the American music industry—recording technology and widespread touring–to disseminate that feeling of “unisonance” ubiquitously across Black America.

Douglas

The songs of the civil rights range from hopeful to grief-soaked, triumphant to profound. And all of them helped lift the message and galvanize the people, and keep the movement moving forward! Music carries a message and brings it into a part of the brain that responds differently to speeches and text. Music can get in, where other forms of communication cannot.

James Brown’s style of funk was powerful, there was so much joy and pride flowing from his music. Black pride was an essential component of the Civil Rights movement. It helped people remember that the movement was not just about injustices and harm and what’s wrong with society. James Brown was celebrating what’s good, about Black beauty and Black joy, Black pride.

There is a lot of great music from the Civil Rights movement that will sting the conscience, that will being hope and unity, that will reveal the harm and lament the injustice. But if you are looking for unapologetic Black joy, you’re going to love James Brown.

Video Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud by James Brown

Douglas

We had a hard time limiting ourselves to the songs we are featuring this morning. Many songs were given a featured place by many people in the movement. There are numerous ‘unofficial anthems’ of the movement. It’s heartening, I think, to have so many songs lifted up as important. It is a testament to the importance of music to the Civil Rights movement.

The Staple Singers’ Freedom Highway, Gil Scott-Heron’s The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, Nina Simone’s Mississippi Goddam, and Marvin Gaye’s Inner City Blues are songs for the playlist I’m going to put out tomorrow – but regrettably did not make the cut for our brief hour together this morning. And white artists like Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger are important. But I want to be sure we keep our attention on the black artists this morning.

What music do you think is the music of today’s movements? Even if it is not music you regularly listen to – do you know about the artists? Have you heard, for example, Childish Gambino’s This is America? Or Shea Diamond’s Don’t Shoot? Are you aware of Kendrick Lamar’s Alright? Aware of the story behind it, the context of it, the message offered?

Pay attention to the music around you, notice how it serves beyond mere entertainment. Music has a way of getting into our brains in a way regular speech or text cannot. Music connects us, uplifts us, unifies us, and moves us forward. What are you listen to these days?

May the music be strong and may the movement be strong. May we be strong together.

In a world without end, may it be so.

—

Postlude All You Fascists Bound to Lose sung by Resistance Revival

Do You Have Enough Love?

Do We Have Enough Love?

Rev. Douglas Taylor

2-15-26

Sermon Video: https://youtu.be/RKg38pB8EKw

“Let your days be the evidence of a heart on fire,” artist and activist Danielle Balfour tells us from our Opening Words this morning. ‘Your days,’ she says specifically. Not something vague like your ‘thoughts and prayers,’ and not something general like ‘your whole life’ – your days – today, even. “Let your days be the evidence of a heart on fire.” In another piece she writes, “What do I do with all of this terrible news?” And she gives a very similar answer: “I will let it inflate my capacity to love.”

Balfour’s message of engagement, of loving your neighbor, of caring about what is going on to people around you and not growing numb in the face of harm and tragedy, … it is a key tenet of liberal theology. As we say now about our theology as Unitarian Universalists: “Love is at the center,” but it should be more than a slogan, yes? How does that look today? Are your days evidence of that love?

I mentioned in my description of today’s service that I’m going to talk about a theologian, but in doing so, I want us to remain grounded and connected to this moment we are living in. There are terrible things happening around us and among us today – does our faith have what we need to see us through? Is our theology strong enough to oppose Fascism, to spur us to rebuke oppression? Is liberal religion up to the task we have before us?

Or, let me frame this from a contemporary artist. Grandson is a modern hip hop and rock musician. He has a song from 2020 called “Dirty” that I discovered about a year ago which frankly inspired this whole sermon. The chorus has a line that led to my title; he sings “Do you have enough love in your heart to go and get your hands dirty?” “Do you love your neighbor?” he asks, “Is it in your nature? Do you love a sunset? Aren’t you fed up yet?” The song is a call for getting active in the face of apathy. Sure, we can say ‘Love is at the center,’ but do you have enough love in your heart to go and get your hands dirty?

We have good historical precedent to answer yes. Unitarian Universalism has a proud lineage of resisting tyranny and fascism. Of revealing hope, of holding out a promise to treat all people – particularly the marginalized and the vulnerable – as beloved and precious. Unitarian Universalism does have a potent message to offer in face of rising tyranny.

And … sometimes our liberal theology lets us off the hook; sometimes it allows us to misconstrue freedom as ‘personal freedom;’ sometimes it shields us from experiencing the discomforts of being complicit and even culpable. We are sometimes accused of being soft on sin, accommodating to evil, tolerant of atrocities, enamored with our own comforts because we say God loves everybody and we all have inherent worth and dignity – even the worst among us. Who am I to judge?

In the early 1900’s Unitarian theologian James Luther Adams asked if our theology was strong enough to oppose Fascism. He pushed us to dig deep into our beliefs and values, to check our mettle against the needs of the time. In his critique, he did uncover an affirmative answer, though he did caution us to be wary of the diversions and perversions so readily available among us.

James Luther Adams was a liberal theologian and ethicist from the 20th century. In the 1920s he graduated seminary and became a Unitarian minister in MA for roughly a dozen years. In the late 1930’s he became a professor at Meadville Lombard Theological School, my alma mater. Almost 20 years later he moved back east and joined the faculty at Harvard teaching Christian Ethics. He wrote several books and essays. He had died a few years before I entered seminary, but his legacy still loomed throughout the school and throughout my reading lists.

In the summer of 1941, when the United States was still playing isolationist to the war in Europe, Adams warned that liberal theology was at risk of being coopted by the culture of middle-class values – namely the value of ‘respectability.’ We were in danger of losing our radical edge in favor of being respectable. He said this as the keynote speaker for a prestigious lecture among Unitarians called the Berry Street Address.

He warned, back then in the 40’s, that we were in danger of losing a central element of our theology that called us to stay fresh, to allow change to overtake us, to be so moved as to make a complete change – to allow for religious conversion. This was not only an argument for being radical in the realms of justice and social change – but of religious and spiritual change as well. He warned us that in over-valuing respectability, we undercut an important aspect of our theological heritage.

I would say when we shift from radical to respectable, we soon become irrelevant. And I am grateful for the radical movements of the 60’s which brought many of our Unitarian Universalist communities back into relevance. And … we’ve been at risk of becoming respectable again in recent years. I echo the concern Adams raised nearly a century ago on this point. And I’ll echo Grandson’s question: “Do you have enough love in your heart to go and get your hands dirty?” Do you have enough love at the center to take risks for the vulnerable, to protect the marginalized, to decenter your comfort and get your hands dirty? Are you willing to grow?

One aspect of what is changing among us, I think, is a shift along the lines of theology from strongly liberal to fiercely liberation. By this I mean: Where Liberal Theology traditionally focuses on personal autonomy and agency, intellectual freedom, and the use of reason; Liberation Theology emphasizes communal freedom, prioritizing the experiences of the marginalized, and a struggle against systems of oppression. My theology leans strongly toward liberal, but my preaching in recent years has become more decidedly liberation.

I have been watching this theological shift happening among us (and within me) for a while, honoring that both liberal and liberation theologies are alive and vibrant among us in our UU communities right now. And I wonder if the dynamic is actually less about the labels of liberal and liberation, and more about this point of shifting out of being respectable and back toward our heritage of being theologically radical.

One particular essay James Luther Adams wrote that has remained a gravitational center among us is a list of five qualities at the heart of Religious Liberalism. https://www.uua.org/lifespan/curricula/wholeness/workshop1/167560.shtml He called them the Five Smooth Stones – a reference to the story of David and Goliath in Hebrew Scripture. I suspect they remain impactful by the fact that they work for both liberal and liberation thought – although written from the perspective of a liberal theologian.

Hear the list Adams made of these five theological qualities: As a liberal religious community we affirm that we are always learning; that there is always more truth unfolding in our understanding. We see that being together matters, relationships are more important than doctrine. We further state that how we are together – how we are in consensual relationship – also matters. We are committed to the notion that to be good we must do good. And finally, we are always hopeful. (For more on the Five Smooth Stones, see this sermon I delivered in 2012 https://douglastaylor.org/2012/05/27/five-stones/) These five points are not a theology of personal freedom, as sometimes happens among us. Instead Adams calls for a communal theology that carries us all.

This is a solid articulation of our theological ground as religious liberals, a statement of how we are human in community together – theologically. And it is that last piece, the fifth point, that will occasionally derail us. ‘We are always hopeful.’

It can be naive. We Unitarian Universalists can allow our optimistic hopefulness to blind us to the depth of our complicity with what is causing harm in the world. But that is something Adams experienced and cautioned against.

Allow me to share the full text from Adams on this fifth point he made about our optimistic hope.

“Liberalism holds that the resources (divine and human) that are available for the achievement of meaningful change justify an attitude of ultimate optimism. This view does not necessarily involve immediate optimism. In our century we have seen the rebarbarization of the masses, we have witnessed a widespread dissolution of values, and we have seen the appearance of great collective demonries. Progress is now seen not to take place through inheritance; each generation must anew win insight into the ambiguous nature of human existence and must give new relevance to moral and spiritual values.” (From J. L. Adams, “Guiding Principles for a Free Faith,” in On Being Human Religiously, 1976)

It is worth noting that Adams spent time in Germany during the mid-1930’s with friends like Karl Barth and Albert Schweitzer who were actively resisting the rise of Nazism. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Luther_Adams He was well aware of our human capacity for cruelty and brutality. When he made a theological claim that we have cause for hope – he was saying we have the resources to effect positive change. We have the resources and need to use them.

To augment this point from other quarters, recall that Helen Keller said “Although the world is full of suffering, it is full also of the overcoming of it.” Or as MLK said “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” Or remember Anne Frank who wrote “I don’t think of all the misery, but of the beauty that still remains.”

Our hope is not encased in denial or shielded by blinders. It is a full-throated hope in the face of trouble. When I was in Minneapolis protesting against ICE last month, I learned several street songs and protest chants. I’ve kept my ears open as I learn more since returned home. And sometimes these songs are angry and profanity-laden. Sometimes they are defiant and boisterous. And sometimes they are calm and hopeful:

Hold on – by Heidi Wilson

Hold on, hold on

my dear ones here comes the dawn.

‘Here comes the dawn,’ they are singing throughout these recent weeks as things have been terrible. …my dear ones here comes the dawn.

The hope they are singing is a companion to the clear-eyed awareness of injustice. James Luther Adams is far from the only person reminding us that our liberal religious commitment to an optimistic hope is not soft or naïve. It is instead a power that spurs us to move closer to the trouble we see. It is a willingness to get our hands dirty because we know our love must show up in the streets, must move alongside the suffering, must companion the vulnerable and share the risk they face.

We are called, because of this hope, because of this love at our center, to go and get our hands dirty. We are called by this love to rise up against hate and get a little messy. Our hope is in recognizing evil, naming it and rebuking it. Our hope is in the clarity of our love.

Friends, our theology does not call us to be among the respected classes. We are not called to whisper sweet platitudes of God’s love to the oppressors. Instead, we are called to remember that our love is radical. Our faith calls us to grow. Our faith calls us to build authentic relationships. Our faith calls us to build just and loving communities. Our faith calls us get out among people in need and get our hands dirty, to let our days be the evidence of our hearts on fire. Our faith calls us to remain hopeful, to choose love, to not hide from evil, but to face it clear-eyed.

To rise, to heal, to grow, to love.

In a world without end,

May it be so.

The System Works as Designed

The System Works as Designed

Douglas Taylor

1-18-26

Sermon Video: https://youtu.be/d_DDPYDuzCY

“This is not the America I love.” I have heard people say. “We’re better than this!” “What has happened to our country? I have heard. When we say this, we are trying to articulate a positive statement that the good country founded on good principles and civic values is not apparent … and that what is going on around us now is, by contrast, not good, not in keeping with those good values, that good foundation that we see.

And I want to let you know there is a flaw in that logic, there’s a flaw in that argument. Our country was founded through the genocide of the indigenous people. Our country was built on the labor of enslaved people. There is growing awareness that our criminal justice system is built around protecting property first, and originally that included slaves – and some argue there are echoes of that still happening today. Capitalism is structured not around benefiting creators and laborers or even society in general – it is structured around benefiting owners.

There is this tension that is in place when we say something “This is not the country I know and love.” Because it is. What we’re seeing now very often has an echo that can very easily and obviously be traced back to some of the flaws, some of the injustices, some of the cruelty that was backed into our country when we started.

But you’re also not wrong. There is a tension here. We as a country came together and wrote promises, saying who we are and who we long to be. Promises about equity and equality and ‘endowed with unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.’ That all people are created good. That was part of it!

There’s a piece in the 1963 speech that King made – that is perhaps his most famous one, “I Have a Dream.” The beginning of it, before he gets rolling, he talks about a promissory note. He said, “we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check.”

He said the ‘architects of our republic had made – with magnificent words in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence – promises and we see this as a promissory note, a guarantee of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He said:

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

He refused to let only the critique stay, but also that we had made a promise for who we could be.

“This is not my America,” we say. “This is not the country I love, what we are seeing in the streets.” … well – yes it is. We are flawed from the beginning. And we have greatness baked into who we could be. But we must work for that part.

The tension is that we have both the rot and the promise at our foundation and we can feed the promise while cutting out the rot. Both are true. When you wonder about what’s going wrong – part of the answer is: things are going as planned. We are at the logical outcome of the trajectory we’ve been on for a while.

But that doesn’t mean we’re done. It means there is a tension in the system. So what are we to do about that? It means we need to participate. We need to build the more perfect union. We need to engage.

In that 1967 speech (Where Do We Go From Here?) that we used as our reading, Dr. King talked about – we would say today – intersectionality. He talked about the triple evils of Militarism, Materialism, and Racism. He wove all three into this one paragraph that I absolutely love:

In other words, “Your whole structure must be changed.” A nation that will keep people in slavery for 244 years will “thingify” them and make them things. (That’s the racism) And therefore, they will exploit them and poor people generally economically. (There’s the poverty) And a nation that will exploit economically will have to have foreign investments and everything else, and it will have to use its military might to protect them. All of these problems are tied together.

The entanglement of racism and poverty has been on most people’s radar for a while, economic struggle lands disproportionally on people of color. But King is also saying poor people are exploited in our current system. Full stop. Not just that poor black people are exploited, but that poor people of every race or ethnicity are exploited. And then he ties the military in by saying the country will need to prop itself up with foreign investments that need protecting – thus a military. King lived through the use of state violence against poor people and against African-Americans in particular. And yes we usually outsource our foreign wars to proxies lately, but who knows, that might change soon. But the militarism evil that he is talking about is not just beyond our borders. It’s happening without our borders against our own people.

King called for non-violence. Often when folks wake up this reality or start calling out this reality, of this tension, of things that have gone wrong, sometimes they’ll lean into King and they’ll talk about his non-violence.

A lot of people remember King for non-violence and remember his speeches and his rallies. But it is incredibly important: King spoke of non-violent direct action. He never just spoke about non-violence. He was not in favor of passivity, of backing down, of non-violence in the sense of ‘I’m not going to get in the middle of anything because that might lead to violence.’ He was very encouraging of people getting in the middle of things, to direct action. To only speak of his non-violence is a perversion of his legacy.

Some of you have been in a class that Rev. Jo VonRue and I are co-leading over the fall. It is a class on democracy that meets online monthly with folks from several UU congregations in the area. The very first class talked about “Effective Strategic Escalation” which talked about various types and levels of protest.

We used Gene Sharp’s analysis. Gene Sharp is a decades-long scholar on non-violent action; and he has, for example, this one book that talks about 198 versions of direct action. He breaks them into three type: symbolic action, noncooperation, and alternative cooperation or Intervention

Symbolic direct action is like a rally or hanging a banner. Non-Cooperation is like a strike or a boycott. Alternative Cooperation or Intervention is like a sit-in or traffic obstruction.

The story we shared with you, “Sunny-side Mary” has some of these elements in it. Sitting in the good seats, that was intervention, that was essentially a Sit-in. When she was wading in the water, that was some symbolic action. It drew the Shady Side folks’ attention and it got something moving symbolically. And when they were all sitting in the fountain that was some alternative cooperation – some intervention, something new and different. (I guess a strike or boycott would be if all the – they had to show up or risk detention – but they could boycott paying attention. That wasn’t in the story.)

Dr. King called people into a variety of styles of non-violent direct actions. He is famous from all the rallies and speeches. But it is too easy to only do symbolic action. And if all you are doing is symbolic action, 60 years later, our country’s oppressors have figured out how to ignore you by now. It’s not enough. It’s good to do and its not enough. You need to have other things going on so the systemic powers will not simply ignore you. We need direct actions that wake people up, that get’s people’s attention, that is coordinated and planned if they are going to be effective. But it needs to be direct action.

And, ultimately, all of that action needs to be accountable to the vulnerable people most impacted by the oppression and the consequences of our direct actions.

Which brings me around to an announcement. I have been invited and I am responding to a call to action. The clergy in Minneapolis have put out a call saying ‘ICE is here and we want you to show up.’ They link their call to Selma when King put out a call for clergy and lay people to come and witness.

It is not lost on me that part of the history of the 60’s and that Civil Rights Movement that a Unitarian Universalist minister James Reeb went down and was killed. And when a white man from the north was killed, that had a different impact on the country than when all the other men and women – the people of color – had been killed and had not risen to the same level of attention.

I am not going to disparage anybody who is dramatically upset by the death of Renee Good, the murder of this white woman. Please also notice all of the black people ICE has killed in this past year.

Part of the systemic effectiveness we are called to is to allow Renee Good’s murder to activate us. We can unpack the racism of that eventually. We’ll get there.

But when King said we need to ‘begin to ask the question …’ – he began asking those questions about the triple evils 60 years ago. Are we still beginning to ask these question? No. We need to keep moving.

I have been invited to go to Minneapolis and to be accountable to the people who are there on the ground dealing with ICE directly.

When I went to Standing Rock almost 10 years ago, I had to specifically come back and say “I never wanted to risk arrest.” There were some folks here who were disappointed that I was not arrested. The badge of having done a resistance means you got arrested.

The clergy at Standing Rock were specifically not invited to do a civil disobedience that would risk arrest. In fact there was one dude who stood up at the training the day before and said ‘and those of us who want to risk arrest, come over the corner and we’ll talk about doing additional things.’

One of the grandmothers, one of the elders went to that circle … and there were a dozen white people sitting on the floor as this elder yelled at them. ‘That is not what we asked you to come do. Our Water Protectors will risk arrest. You are here to witness.’

I have been called to Minneapolis, I don’t know what they are going to ask of me. But I will be accountable to the people on the ground who are dealing with this directly. It has been made clear, it is not safe to go to Minneapolis right now. If you are a person of color or if you have a disability or if you are an obviously Trans person it may not be a good choice for you to come to Minneapolis to respond to this call. It is not currently safe in Minneapolis to be a protestor, to be an immigrant, to be racially-profile-able.

And we (attending this call) need to be accountable in any direct action we are invited into to the people who will be impacted by the consequences of that direct action. That’s incredibly important.

Yes, the injustices and oppression we are seeing today are cruel and beyond the pale. This is not the America we want. It is the America we have, the systems of oppression and injustice from our inception are echoing into our current situation. The system is working as designed. And there is another layer of design – a promise of equity and opportunity and liberty – a layer of design we need to engage and enact and make real. We need to build the more perfect union.

May we hear the complaint as well as the call. May we learn that these calls are coming to you, to me; and that it is our work to respond, to build that new America that hope can be.

When I go to Minneapolis I want to carry you with me. I’m not going to go alone. This is the stole I will be wearing (a “side with love” stole.) I want to bring you with me. I don’t know exactly how your unique theology will respond to this but can you bless this? Can you bless me? Can you pray for me? Can you imbue this stole with your wishes for what might happen, what I might encounter, that you will be with me when I am there on the streets.

If that means you might come up and touch the stole, say a prayer, send good energy, drop extra money toward the discretionary fund. I don’t know how you bless things. But please, if you are willing, offer some blessing so that I can bring you with me when I go to Minneapolis, and that they will know that we are with them; and that we care about them and this world and this society that we are recreating – the whole system.

May we lean in to the call and to the voices of those most marginalized and targeted. May we embrace the holy work of caring for each other and for those in need as we build the more perfect union.

In a world without end, may it be so.

Tea and Purpose

Tea and Purpose

Rev. Douglas Taylor

12-14-25

Sermon video: https://youtu.be/wS0h-ziD9V4

The amazing Terry Pratchett once wrote: “There’s always a story. It’s all stories, really. The sun coming up every day is a story. Everything’s got a story in it. Change the story, change the world.” (Terry Pratchett, A Hat Full of Sky)

As Pratchett suggests, we do well to pay attention to the stories we are telling ourselves about the world we live in and the world we long to live into.

Last week we talked about Star Wars and the power of hope. One of the things we saw in those stories was how resistance shows up against the forces of Empire. Star Wars is a form of dystopian fiction. Dystopian literature offers a bleak perspective on the future – things have gone wrong and now we need to work to make it better. Good dystopian fiction will go one better to reveal what is going wrong now, not just in an imagined future. It will be about our present condition more than anything else.

Today I want to talk about some utopian fiction. And in a similar vein, good utopian fiction reveals not just some imagined happy future, but how we are living with the seeds of that future even today. “Change the story, change the world.”

The story I am excited about this morning is about robots. I will confess, I’ve never been a huge fan of robot-based science fiction. And upon reflection I think that has to do with the way robots have been portrayed in science fiction over the years.

One of the things about stories is how they have a surface level entertainment and a deeper level of impact. On the surface, a story about robots may be a fun exploration of technology and imagination. On a deeper level, robots offer a mirror to explore what it means to be human. When Science Fiction leans into a character who is non-human, the author is able to help the reader better understand what it means to be human.

Isaac Asimov offered the classic version of robot stories. For Asimov, robots were an exploration into ethics and logic and the hope for a better future for humanity based on ethics and logic. Asimov wrote his robots as tools or servants to humanity. And while he did critique the premise in some ways – that was the premise. Robots were the perfect servants.

Later versions of the genre had the robots take on different roles. Think about The Robot from the Lost in Space series: “Danger! Danger!” The Robot was a powerful and loyal piece of equipment. Think about The Terminator, who was really just a weapon – and then remember how most advances in drone technology are rooted in military research these days. Think about the Droids in Star Wars who were really just a plot device and sometimes comic relief. And then think about the way Gene Rodenberry’s Star Trek portrays the character of Data as a sentient being with relationships and a unique place in the crew. Data was the first (and until recently, the only) robot I enjoyed.

The Monk and Robot series by Becky Chambers offers a radically different robot from the loyal equipment or perfect servant of earlier versions of this literary mirror. Where Asimov’s robots are essentially tools of humanity and society, Chambers’ robots are peers with humanity seeking purpose and community. Where Asimov’s robots are stand-ins for a conversation about racism and law, Chambers’ robots are conversation partners on the topic of freedom and liberation.

And most alluring for me is that freedom is not an either/or scenario – it is not an apocalyptic uprising of the machines. They do ‘rise up’ but their freedom frees the humans too. And that is how this story changes the mirror of what robots reveal about what it means to be human.

The description on the inside jacket of this book categorized as ‘cozy sci-fi’ tells us this:

It’s been centuries since the robots of Penga gained self-awareness and laid down their tools. Centuries since they wandered, en masse, into the wilderness, never to be seen again. Centuries since they faded into myth and urban legend.

One day, the life of a tea monk is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot has one question: “What do people need?” But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. They’re going to need to ask it a lot.

How would you answer? What do you see that we need?

I mentioned near the beginning that this is a utopian story. Part of the premise as the book begins is that the people have resolved their basic needs. There is no poverty, no inequity on injustice leading to homelessness or hunger. It is a society in which everyone basic needs are met. In a world where people have what they want, what more do we need?

In the second book, there is a scene when the robot, Mosscap, first comes to a community and asks it’s question: “What do you need?” The small town of people who turned up to see the oddity of a robot were confused by the question at first. Nobody quite knew how to respond.

After a long pause, a bearded man piped up from the back of the crowd. “Well, um … I need the door to my house fixed. It’s a bit drafty.” (PCS p23)

Sometimes it can be hard to think beyond the immediate needs of our daily rounds. What do you need? Maybe not ‘what do you need help with?’ Maybe not ‘What do you need a robot to do for you?’ Because I don’t have a real robot tucked up here in the pulpit with me. And I’m not so good at fixing your drafty doorway. So what do you need? Really?

I imagine many answers in our current situation might land in the category of righting a wrong, answering an injustice, fixing a gross inequity. I need ambulance rides to be fully covered by insurance and for teachers to be valued more than celebrities. I need oligarchs and abusers to be held accountable and removed from power. I need my society to really care for the wellbeing of all the people in our society.

So, if that were accomplished, as is suggested in our little novel about a tea monk and their robot friend, then what would you need? Pretend we’ve solved our injustices and we live in a Star Fleet type of universe. What do you need?

This begins to drift into theological territory. What is the Human Condition? Many theologies are built around an assumption of sin or fallenness and how awful we are compared with God and what God expects of us. I don’t have time for that sort of sour thinking. Yes, we are imperfect and broken, but not is a sinful or bad way worthy of judgment. We are imperfect and broken in the way all the world is.

I believe our Human Condition is one in which we need to be loved – and we are loved. We may forget this truth or trauma can chased this truth from our knowing, but we are. I believe our Human Condition is one in which we are intrinsically part of the holiness that pervades the whole universe. We are interconnected – thus what I need is not only what I need, but what we need. And we need each other. I think any answer to the question ‘what do people need?’ must include the answer: each other. We need mutual thriving.

In this story I’m inviting you to read, the author makes multiple references to our need for each other. It shows up when the story talks about various things from interdependent ecosystems to friendships. What do people need? Each other.

One of the characters is the robot, the mirror of humanity revealing a deep truth about ourselves. The robot brings the question and raises thoughtful and emotionally mature reflection on the responses it hears from the humans. The other character is Dex, the tea monk.

Let me tell you a little about the work of a tea monk. Dex the tea monk travels from town to town helping people. They set up a small booth in the town market when they arrive. The booth has comfortable places to sit and relax, and it has tea. People visit a tea monk to talk through things they are struggling with. Maybe it is a grief or a confusion, perhaps they just need to talk through a decision they have to make. Usually people simply need a bit of companionship and a space to relax. Dex offers people empathy and they offer a cup of tea. Dex gives people what they need.

“What do people need?” the robot asks. Both the tea monk and the robot are in the business of figuring out what people need. Perhaps it is your business as well. What do people need? Each other, certainly.

In a cozy science fiction story where people’s basic needs are met, where folks don’t need to fight against Empire or join the resistance – they still need things. Surprisingly, what people need to fight Empire is also what people need in this Monk and Robot story – mutual thriving.

Later, during the book discussion I’m planning in January, we will talk more about mutual thriving as well as topics of economy, ecology, freedom, pleasure, our relationship with nature and with technology, as well as the meaning of life. And I’ll serve tea. I promise.

For now, I leave you that question to ponder. What do you need. May you uncover surprising answers as you wind your way through this holiday season.

In a world without end, may it be so.