Every Mind Was Made for Growth

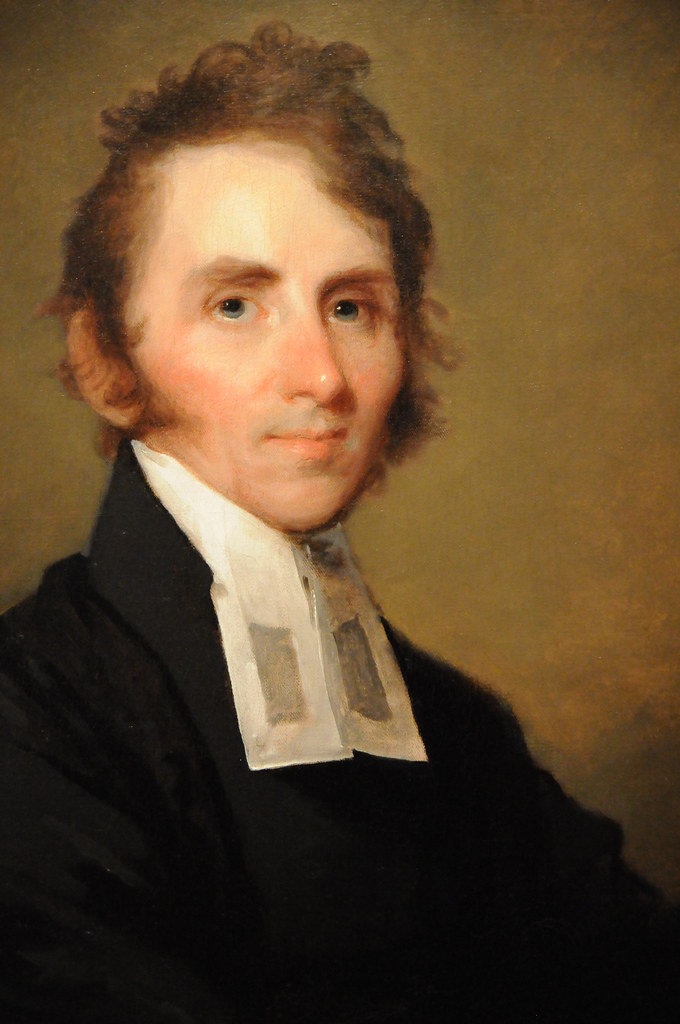

Rev. Douglas Taylor

5-19-19

“Every mind was made for growth, for knowledge,” says William Ellery Channing, “and its nature is sinned against when it is doomed to ignorance.” Our capacity for spiritual and intellectual growth was central for Channing. It was a theological stake in the ground for him.

Channing preached his Baltimore Sermon two hundred years ago in 1819 – on May 5, I will add, (so, two hundred years and two weeks ago.) Six years later, in 1825 – on May 25, I will add – the Unitarians organized themselves into the American Unitarian Association. The month of May is particularly rife with institutional dates for us.

More importantly, there are some key points in that Baltimore Sermon which carry forward to today, which have shaped out religious identity as Unitarians and Unitarian Universalists over the decades. “Every mind was made for growth,” Channing said.

“What does God sound like?” my oldest child once asked me.

So, of course, I dragged my then 5-year-old child outside and sat with them in the grass and said, “Listen. What do you hear?”

“Wind.”

“Good. What else.”

We were quiet for a moment. “chirping.”

“Yes, that’s birds and squirrels. What else.”

Silence stretched as we listened. “I hear insects buzzing.”

“Good. Yes. All this is what you are listening for.”

“So, God sounds like nature?”

“Yes.” I replied, “But is there anything else you hear”

“Well, cars out on the road… And you and me talking.”

I grinned. “Yes. All of that. Everything.”

I don’t remember exactly what prompted this conversation between us. I do not remember what we talked about next. And honestly, I only remember the conversation because they reminded me of it some years later. It was part of the sense of wonder they picked up as a child which still feeds their sense of what it means to be part of the universe, what it means to participate in the holy, a starting point from whence their sense of God has matured as the years have gone by.

In retrospect, I think I was striving to instill wonder and curiosity rather than instill a fact. I was endeavoring to not “stamp [my] own mind upon the young, but too stir up their own.” (STL #652) I’m not sure our conversation then is representative of my theology now. But it was a snapshot for both of us, a moment in my evolving understanding and in theirs.

How was it for you? What opened you up to awe and wonder as a child or at a point when you were younger? Where did things open for you? Is there a moment or two you can recall that serve as a launching point for your intellectual or spiritual curiosity?

These questions matter; because who you were when you were 5, asking questions and awakening to wonder, is still there in you. As Sandra Cisneros says (in her poem eleven) “Because the way you grow old is kind of like an onion or like the rings inside a tree trunk.” It’s why our Family Ministry program is for all the people in the congregation and beyond – not just our children. Because we all have our questioning childhood selves within us still.

So how was it for you? Where did things open up for you? “Every mind was made for growth,” Channing said.

William Ellery Channing is considered the founder of American Unitarianism for his landmark sermon, “Unitarian Christianity” in 1819. He broke new ground. He brought forth a new identity. He was a reformer. Channing’s Baltimore Sermon, as it is better known because that is where he was when he delivered it, outlined the radical beliefs that were coalescing within a number of liberal religious communities in New England. He delineated the theological rejections and affirmations that characterized the group of people who soon after became known as Unitarians.

Conrad Wright, editor of the book, Three Prophets of Religious Liberalism: Channing Emerson, Parker characterized it this way: “Channing took the liberal wing of New England congregationalism, fastened a name to it, and forced it to overcome its reluctance to recognize that it had become, willy-nilly, a separate and distinct Christian body.” (p3)

This sermon was a two-part sermon of which most people recall only the second part. I will pause here a moment to reflect that while most sermons run about 15-20 minutes, Channing talked for over an hour. (Mendelsohn, Reluctant Radical 160) It was a long sermon. Primarily, the first part of the sermon emphasizes reason as the best tool for the study of scripture. “We are particularly accused,” Channing writes, “of making an unwarranted use of reason in the interpretation of Scripture.”

Channing, in the second half of the sermon, then lists out several doctrines found in scripture when reason is so applied. The first two sound like this:

In the first place, we believe in the doctrine of God’s UNITY, or that there is one God, and only one.… [Secondly,] We believe that Jesus is one mind, one soul, one being, as truly we are, and equally distinct from the one God. We complain of the doctrine of the Trinity; that, not satisfied with making God three beings, it makes Jesus Christ two beings, and thus introduces infinite confusion into our conceptions of his character.

And while this is the heart of why we have the name Unitarian, this is not the heart of what has carried forward through the decades as our religious identity. Modern-day Unitarian Universalists are not doctrinally wedded to the theology of God’s unity. We have a plurality of beliefs about the nature of God. What has followed through as a thread to today is the theology Channing elucidated about what it means to be human.

William Ellery Channing preached a radical theology of human nature. This was a rebellion from the Calvinist theology of the day, a theology that spoke of humanity as being totally depraved and in need of God’s grace, of a humanity bound to sin and with no power by which to change the situation. Only though the grace of the all-powerful God above could a person be saved.

In his sermon, Likeness to God, Channing writes,

What, then, is religion? I answer; it is not the adoration of a God with whom we share no common properties; of a distinct, foreign, separate being; but of an all-communicating parent. It recognizes and adores God, as a being whom we know through our souls, who has made man in his image, who is the perfection of our own spiritual nature, who has sympathies with us as kindred beings … (He goes on to say,) Above all, adore his unutterable goodness. But remember, that this attribute is particularly proposed to you as your model; that God calls you, both by nature and revelation, to a fellowship in his philanthropy; that he has placed you in social relations, for the very end of rendering you ministers and representatives of his benevolence…

Channing, here demonstrates how radical his Christianity was at that time, indeed it might still seem radical to most Christians today. God is a model of goodness. We are beings who do good because we have within us the image of God, who is “unutterable good.” We are not disobedient sinners, flawed creatures, depraved souls bound to sin with no good in us. We each have what Channing called the Divine Seed within.

Channing didn’t claim we did only good deeds. He saw in us the connection of God; he didn’t claim we were God. That came later, through Emerson and others after him. Channing and the other Unitarian Christians of that time were Arminians. Arminianism is the doctrinal position that denies election and original sin, and supports the doctrine of free will. It is basically anti-Calvinism, if you will. Jacob Arminius was a Dutch reformed theologian from the 1500’s who said that people could respond to divine grace. He basically said everyone could be saved. John Calvin was saying, “No, only a select few could be saved, a pre-selected few in fact.”

One could characterize it this way: Calvinists believed that every human being was born in original sin. It is like saying you begin life on a train speeding toward hell, totally depraved and unredeemable, and only a few have a chance of getting off. Arminianism – and the formative Unitarian theology of Channing – says you start your life on the platform and can choose which train you get on, and perhaps you can even change trains during the trip. There is no limit to the number of folks who can get a ticket for the heaven bound train.

Unitarianism’s message of the innate dignity and goodness of human beings grew from the Channing’s early articulation of Unitarianism. The first of our current Seven Principles of Unitarian Universalism: “to affirm and promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person,” is an echo through the decades of Channing’s theology of human nature.

When Channing said “Every mind was made for growth,” he was declaring that to be our precious inheritance as human beings. It is not sin that we inherit, but our capacity to grow and become closer to God in our goodness. He asserted that the ‘Image of God’ we all carry is our essential capacity of the mind. My favorite line from the Baltimore Sermon is when Channing says: “God has given us a rational nature, and we will be held to account for it.”

I often hear from you who worship here that you appreciate a sermon that gives you something to think about, that stirs your intellect. Do you recall what opened you up to curiosity and wonder as a child? Is there a moment or two you can recall that serve as a launching point for your intellectual or spiritual curiosity? How was it for you?

That responsive reading in our hymnal (SLT #652) by Channing comes from a talk he gave in 1837 to the Sunday School Society. It is his vision of religious education, and it still serves to this day as our vision for Family Ministry. Indeed, it serves as the vision I have for my preaching. “The great end in religious instruction is … Not to make them see with our eyes, but to look inquiringly and steadily with their own; not to give them a definite amount of knowledge, but to inspire a fervent love of truth.”

The journey continues. Let us move forward boldly.

In a world without end,

May it be so.